Allergies are commonly encountered through their symptoms—sneezing, wheezing, itching, dripping, swelling—bodily responses that may be mild, debilitating or sometimes life threating. But what is an allergy? And what strange energies does this term set in circulation?

An allergy is often described as the body’s overreaction to a substance – dust, pollen, spores, nuts, milk, seafood – that is ordinarily harmless. In medical terms an allergy is a breakdown in the protective mechanisms of the immune system, which are directed at ‘the wrong target.’ A foreign entity (or allergen) which is normally easily incorporated (as breathable air, nutrition, etc.) is mistaken as a threat, triggering an immune response.

The field of immunology, which studies allergy along with other immunopathologies, is traditionally known as the science of self/non-self distinction. Behind this lies the notion of an ‘immunological self,’ that naturally knows itself, and works to maintain and defend these boundaries. Allergy is considered pathological (and sometimes even termed ‘paradoxical’) because it makes explicit the capacity of the immune body for misrecognition and error, resulting in self-harm.

The image of a pure self under threat has implications beyond the medical sciences. As theorists such as Esposito, Derrida and Haraway have argued, immunity operates as a powerful socio-political metaphor for constructing and policing boundaries between inside and out, community and threat, normal and pathological, in the name of public and environmental health.

But if we turn to the origins of the word allergy at the start of the 20th century it is possible to trace a different approach to immune bodies and their social and ecological imbrications.

The word allergy is derived from Greek allos—other, different, strange—and ergon—activity, energy, work. This energetic account of allergy emphasises both the activity of bodies and their susceptibility to shift in intensity and orientation. The word was created by von Pirquet in 1906 to refer to the ‘altered reactivity’ undergone by a body after multiple exposures to an antigen. What is particularly striking about Pirquet’s account of allergy, is that he does not intend the term to refer to a particular type of illness, such as hay fever, or even to immune disease more generally.

Rather as Jamieson argues in her article, ‘Allergy and Autoimmunity: Rethinking the Normal and the Pathological,’ for Pirquet, allergy describes the general capacity of a body to alter its reaction, a characteristic he thought was essential to all immune responses both protective and pathological. Thus, it is not the ability to identify threat that is fundamental, but rather the flexibility of immune bodies, their capacity to undergo energetic transitions in response to a shifting environment. On this account, the boundaries between self and other, nutrition and toxin, inside and out, are not fixed but materially enacted in shifting, contextually sensitive ways.

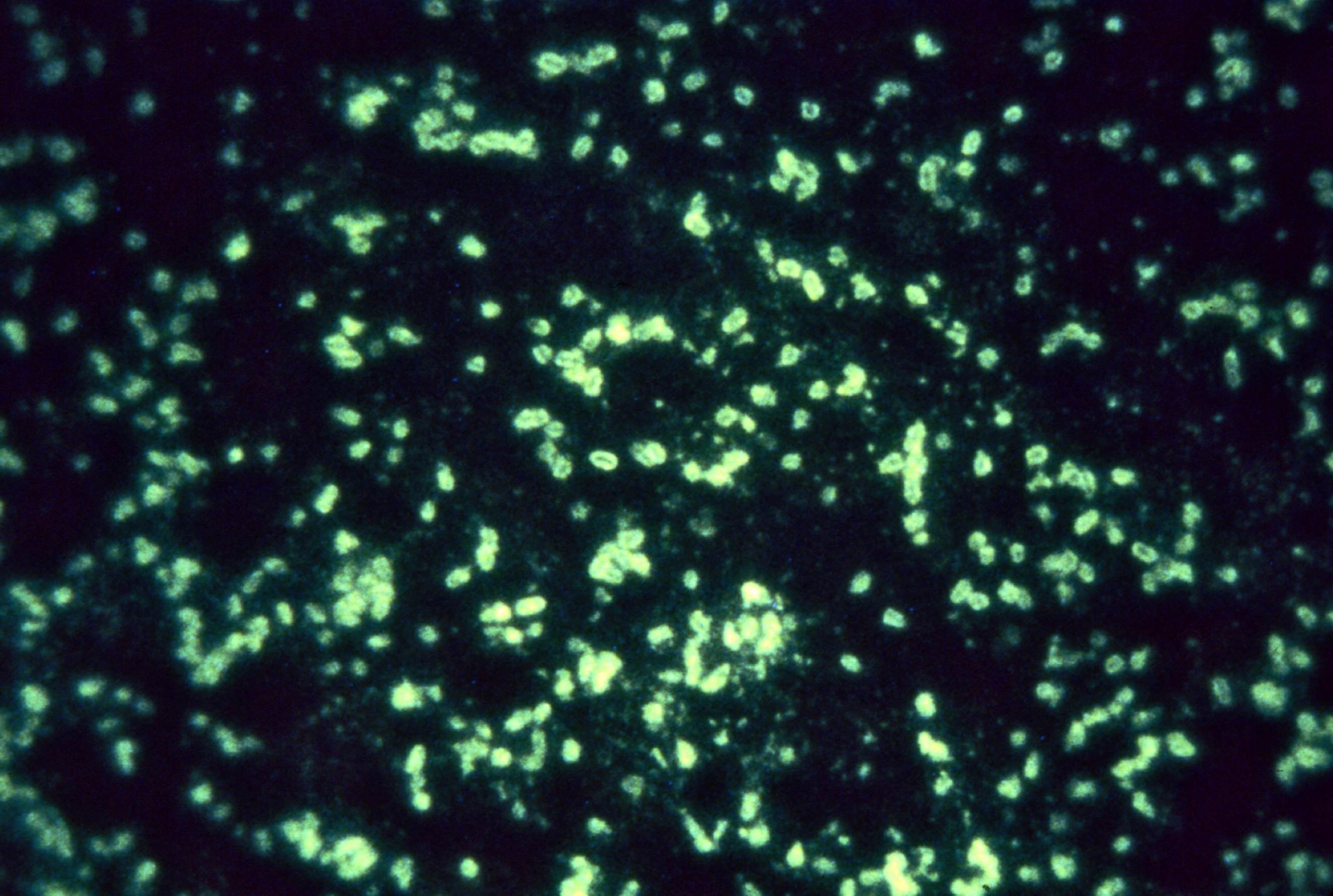

This understanding of the immune body, in dynamic relation with its surroundings, aligns with many ecologically orientated accounts of allergy elaborated in the life sciences today. So, for example, sensitisation is the temporal process whereby the immune system gradually comes to notice, or learn to be sensitive towards, an entity, which was previously incorporated or tolerated. Here the status of the entity as threatening is not fixed. Rather, sensitisation arises through a series of encounters, a temporal window that emerges or might pass, depending on patterns of exposure, and wider environmental shifts. Nor is it always possible to say that an allergy is simply the immune system directed at the ‘wrong target’ since some allergic reactions, such as reactions to some insect bites or plants, may have echoes of a protective function in their evolutionary history.

Negotiating these shifting uncertainties is part of living with allergies. It is often the ubiquitousness of potential allergens circulating in the air we breathe, the food we eat, dispersed on household surfaces, exchanged through bites and stings, that prove so difficult to navigate for those affected. Food allergy guides and pollen counts are ways of noting down, and bringing to conscious public attention, material flows and exchanges we habitually forget, but which our bodies can learn to notice, sometimes with disorientating effects.

Thus allergy reminds us of the agency of our biological bodies to negotiate with their surroundings, and in the process to reconfigure social relations in strange and unanticipated ways. Allergic reactions have the power to cancel actions, unravel plans, and reassemble the ways we work, play and gather together at table. But allergy is also a small part of a much wider palate of ongoing immune negotiations, which for the most part, are underway below the threshold of our attention. At the heart of an allergic reaction lies an ambiguity—an action-back-again, an aversion, acquaintance, reverberance, and echo.

Undine Sellbach